There are hundreds of thousands of new research being published every day. How do we know which one is good ? Sometimes there are many different articles exploring the same question, but giving opposite conclusions. So, How do we know which one to trust? It is obvious that not all evidence is of the same value, and in this article we will explore that hierarchy of evidence. Medical students and doctors have to navigate a vast sea of data to identify high-quality evidence that can truly guide patient care. Furthermore, understanding how to decide if evidence is “good” or “bad” involves looking beyond just the study design to evaluate its quality, appropriateness, and feasibility [2]. The different types of study designs, researches are discussed in more detail in a separate article here.

The Structure of the Hierarchy of Evidence

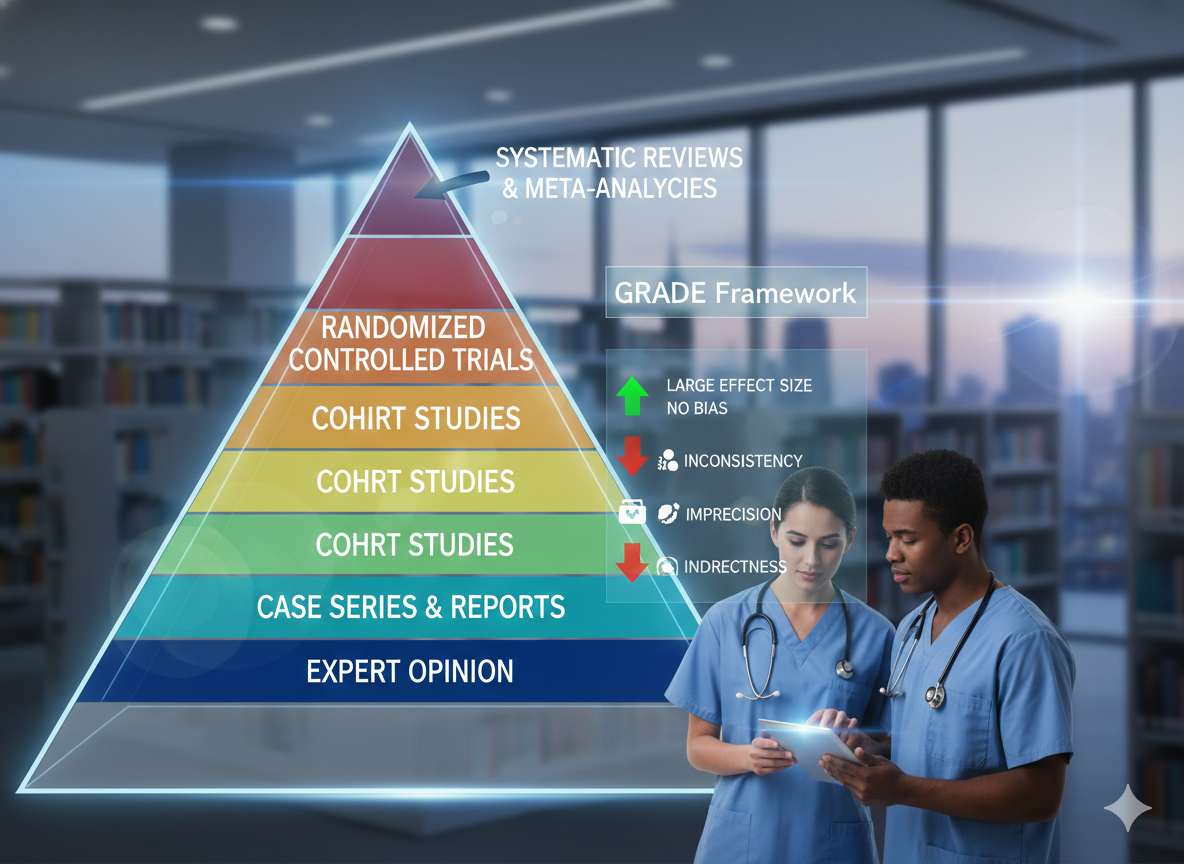

The hierarchy of evidence is typically represented as a pyramid, where study designs at the pinnacle are considered to have the lowest risk of bias.At the top, systematic reviews and meta-analyses statistically pool data from multiple randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to provide precise treatment effects. Below these are individual RCTs, which are the gold standard for testing therapy due to their ability to control for both known and unknown prognostic variables through randomization [3], [4].

- Systematic Reviews/Meta-analyses: The strongest scientific base, summarizing the magnitude and precision of evidence [3].

- Randomized Controlled Trials: Experimental designs that minimize bias and achieve high internal validity [4].

- Observational Studies: Includes cohort and case-control studies, which are often better for determining etiology or rare outcomes [3].

- Case Reports and Series: Descriptive accounts that lack a comparison group but are useful for hypothesis generation [4].

- Expert Opinion: Considered the lowest level of evidence, as it is highly susceptible to personal bias [3].

Deciding if Evidence is High-Quality: The GRADE Approach

A common misconception is that a study high on the hierarchy of evidence is automatically “good” [1]. In reality, the quality of execution is just as critical as the design itself. In contrast, Modern EBP utilizes the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) system to standardize the quality of evidence and strength of recommendations [2]. Under GRADE, RCTs start as “high-quality” evidence, while observational studies start as “low-quality” [2], [4].

Factors that Adjust Evidence Certainty

Evidence certainty is not static; it is modified upward or downward based on specific domains [2]:

- Risk of Bias: Limitations like failure to conceal allocation or lack of blinding [4].

- Inconsistency: When different studies on the same topic show widely varying results [4].

- Indirectness: The study population or outcomes (surrogates) do not match the critical patient-important outcomes [2].

- Imprecision: Results based on small sample sizes with wide confidence intervals [4].

- Large Magnitude of Effect: Evidence can be rated up if observational studies show a very large, consistent effect [4].

Absolute Risk and Patient-Important Outcomes

Effective translation of evidence requires a focus on absolute risk rather than relative risk [2]. For instance, a 50% relative reduction might be trivial if the baseline risk is very low. Furthermore, clinicians must prioritize patient-important outcomes—like quality of life or severe exacerbations—over surrogate markers such as lab values [2]. Moreover, for an intervention to be truly “Gold Standard,” it must be evaluated for its effectiveness, appropriateness for the recipient, and feasibility within the clinical environment [3].

| Feature | Relative Risk (RR) | Absolute Risk (AR) |

| Definition | Compares the risk of an event among those with a specific exposure vs. those without3. | The actual probability that an event will occur over a specified period4. |

| Example | “Drug X reduces the risk of stroke by 50%.” 5 | “Drug X reduces the risk of stroke from 2% to 1%.” 6 |

| Clinical Impact | Often exaggerates small effects, especially when baseline risk is low7. | Provides a realistic view of how much a treatment benefits an individual patient8. |

| Patient Decision | Harder for patients to grasp the true benefit. | Essential for shared decision-making and informed choices10101010. |

References

- Nolet PS, Emary PC, Murray J, Harris GH, Gleberzon B, Chopra A, et al. Conceptualizing the evidence pyramid for use in clinical practice: a narrative literature review. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2025;69(3):238-254. View Source

- Chu DK, Golden DBK, Guyatt GH. Translating Evidence to Optimize Patient Care Using GRADE. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(12):4221-4230. View Source

- Evans D. Hierarchy of evidence: a framework for ranking evidence evaluating healthcare interventions. J Clin Nurs. 2003;12(1):77-84. View Source

- Petrisor BA, Bhandari M. The hierarchy of evidence: Levels and grades of recommendation. Indian J Orthop. 2007;41(1):11-15. View Source

- Bigby M. The hierarchy of evidence. In: Williams HC, Bigby M, Herxheimer A, et al., editors. Evidence-based Dermatology. 3rd ed. Boston: John Wiley & Sons; 2014. p. 30-32. View Source

- Li SA, Alexander PE, Reljic T, Cuker A, Nieuwlaat R, Wiercioch W, et al. Evidence to Decision framework provides a structured “roadmap” for making GRADE guidelines recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;104:103-112. View Source

Leave a Reply